Episodes

Monday Sep 03, 2018

Episode 023 - Clericalism, Sex Abuse, Addiction, and Hope

Monday Sep 03, 2018

Monday Sep 03, 2018

Discussion notes:

We start to discuss what everyone in the Catholic Church has been discussing for over a month now, which is the new storm of revelations about sexual abuse of children, youths, and seminarians by priests and bishops.

Parallels between modern day and the 17th century. Nicolaus Steno (the subject of our last podcast) lived in a tumultuous time, and many of his contemporary churchmen, Protestant and Catholic both, do not cut an inspiring figure on the stage of history. Steno tried to live a better life, but it's easy to see his heroic efforts as useless and even a bit misguided. He likely wore himself to death conforming to an ideal that was not quite what Jesus of Nazareth said or intended. (You can say that about many priests in the history of the Church; Michael McGivney and Augustine Tolton are arguably analogous figures here in America.)

Why are we bringing this up on this podcast? The purpose of the podcast is to explore whether faith and reason are compatible. Since both Bill and I believe that the Catholic faith is both reasonable and true, we have and haven't made a secret of the fact that there is an apologetic (in the technical sense of "Christian apologetics") aspect of what we're doing here.

Clerical scandals such as the one that we're facing now are an impetus to some people to reject the Catholic faith as, analogously, the misbehavior of leading members of other faiths, political, and philosophical movements can lead others to reject those as well. We feel it worth while to take one podcast to examine whether that makes sense rationally as well as emotionally.

The collapse of cultural Catholicism in perhaps its last bastion, Ireland...more on this later.

Bill: "All creation is crying out for a new day of change..."

Why I find the 17th century so depressing...a focus on external statements of faith rather than conversion of heart. The massive hypocrisy of Christians fighting war after war against other Christians, whether in the name of their own religious doctrine or, even more so as the century wore on, simply using that as a cover for their own petty political goals.

The conflict between faith and science depends on a lack of intellectual humility. It's a difficult human weakness to overcome (difficult, not impossible) to actually take the observations and reasoning of others seriously and let it influence one's own thinking, rather than just bulling ahead and believing what one prefers to believe.

Paul's followup:

Why clerical scandal is not intrinsically a logical argument against faith. Why nevertheless it is certainly a problem in an indirect sense: if these men can't or won't live up to the standards of Christianity, how can others?

The long decay of the medieval model of the Church, with bishops as wealthy, powerful political figures. The intrinsic tension between this model and the New Testament, recognized throughout the centuries. The ease with which prelates in such a scheme can get caught up in contemporary intellectual currents. The 20th century myth that sexual activity (and a great many other things, like consumer goods and hour long automobile commutes) is a necessity like eating or sleeping. The temptation to enter the priesthood for cultural reasons and to be an authority figure in one's community.

Problems on both the "liberal / progressive" side of modern culture and "conservative" side. Liberal: to reject the testimony of history and wave about in the current of contemporary opinion. Conservative: to adopt a conformist attitude that's primarily about not doing things proscribed by an older culture and one's contemporary conservative subculture. Both attitudes lack strength. One gives in to the noise in the broader culture; the other, being cut off from the real God of love and action, can find itself lacking the ability to live up to the negative goals of celibacy or sexual exclusivity.

What do WE do about it all?

Is there a way to volunteer to help the victims in your diocese? Are you in, or should you get into, a position to help change the way the institutions of the Church--or any other church or organization you are part of and care about--work so that this sort of thing is avoided in the future?

If not, or if a frank discernment of your life situation pushes you in a different direction, what else can you do to "look after widows and orphans in their need" (James 1, reading from last Sunday)? What in your life is most important that you're not doing? What do you need to weed out in order to focus on that?

I myself recognize that in the tension between 1) my work: my consulting, my writing, my scholarship and 2) my private life, which is in desperate need of focus and effort to make it more livable and worthy of Jesus Christ, I think I am also badly in need of 3) finding additional ways to serve others. Where do I do that and how?

If YOU happen to be a victim of sexual or physical abuse, please report it and please find help. You have been wounded, and there are places where you can find healing.

Monday Aug 20, 2018

Episode 021 - Hypocrisy and Geology: Battlegrounds Between Faith and Science

Monday Aug 20, 2018

Monday Aug 20, 2018

Bill and I start off by discussing some of the reasons why there is such animosity against faith and such a tendency to credit the claim that science and religion are mutually incompatible.

I think we miss a great deal of the point if we do not take into account the relentless critique Christianity has mounted OF ITSELF over the past half millennium. The Reformation splintered the Christian nations and sparked unprecedented bloodshed between Christians. There had been terrible episodes before, but these wars, culminating in the Thirty Years' War, were on a new scale. The massive hypocrisy of Christians killing Christians, and the continuing hypocrisy of Christian clergy enjoying positions of wealth and privilege in both Catholic and Protestant nations, sparked further critique, leading to the Enlightenment and modern liberalism and progressivism. I ask you...do you think anything like modern progressivism, which bases itself on advocating for the poor and the repressed, could have arisen except as a Christian critique of Christianity?

In any case, we continue down to the present to be living in the dwindling, waning days of that union between Church and State, even in the US, and the scandals from that are still with us, as we know this month in Pennsylvania and with the spectacle of Cardinal McCarrick. That provides powerful impetus to look for other sticks to beat Christianity with.

It doesn't help that there are also people, in numbers enough to be visible, who really do espouse a form of religion that is contradictory to science. The Bible itself makes no claim to be the only book worth knowing, but the post-Reformation world has quite a few people willing to make that claim on its behalf.

Turning back to the intellectual issues within the debate itself, I bring up the question: why does so much of the fracas around science vs. the Bible center on biology, when the real question is the Bible vs. geology? Biologists have no real basis for determining the rate and overall progress of evolution if they were not given access to the fossil record and geological time scale...by geologists. Further, there is a great deal more of the Bible that makes claims about geology than about biology. (It's still an extremely small fraction, but of that small fraction...)

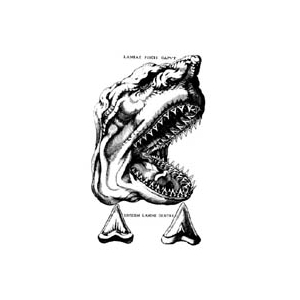

In fact, as the science of geology got started with people like Nicolaus Steno (his sketch of a shark and shark's teeth is the image for this episode), one of their first tasks was to try to evaluate the record of stones and sediment for evidence of Noah's Flood. One of the first crises in geology was dealing with the failure of this quest to find evidence for a global flood (which may or may not be an accurate translation of the intent of the writer of that part of Genesis, but that's another story).

Monday Jun 11, 2018

Episode 011 - Intellectual Citizenship (part 2)

Monday Jun 11, 2018

Monday Jun 11, 2018

We start off unpacking the climate change example further and provide some additional context from political science and seismology. The point is to use climate change as an object lesson in how to break down a big issue at least a little bit, which is what a good intellectual citizen needs to do.

That still leaves us with a picture of intellectual citizenship as a really, frighteningly large responsibility for all of us to try to bear. We spend some time discussing the other side of the issue: we either live in a universe with no loving Creator or moral principle of compassion, in which case it hardly matters what we do or don't do, or else we live in a universe that does have such a Principle, in which case our best effort is good enough, because that Principle has things well in hand no matter what we do. If we let that sense of security sink in, that frees us to start with whatever issue attracts our attention first and go from there. We can take almost any example and infer some principles from that, which can be taken to other problems in the world.

Another point inspired, at least indirectly, by The Death of Expertise is the thought that all of us...certainly all of us who have an interest in the subject matter of this podcast...can, should, and probably already have become experts in something, so that we have offer something back to the world. That very expertise also gives us a lot of grist for considering the work of other experts and coming to some sort of judgment as to whether they are fulfilling their obligations and are more or less trustworthy.

Paul then asks Bill, in his personal expertise in journalism, for some pointers on how to judge media. Bill promises to discuss it more in the future, but takes some time to lament the decline many of us perceive in journalists' willingness to report as opposed to opine and engage in punditry.

Bill asks Paul to close out the podcast with a meditation on how model-based thinking could apply to religion as well as science. One prominent way is to consider how we use the examples of the lives of figures in Scripture and the saints to infer models of how human life can go. We don't get very far if we try to replicate another person's life exactly, and yet there are principles we can abstract from the examples of the saints that can help us on our way.

Apparently, we have not even touched on the issue that inspired Bill's original question about "intellectual citizenship." Whether we do that next episode remains to be seen.

Monday Jun 04, 2018

Episode 010 - Intellectual Citizenship (part 1)

Monday Jun 04, 2018

Monday Jun 04, 2018

Bill and Paul dive into a very simple question posed by Bill over email: "Please describe more what is intellectual citizenship?" That of course opens up a question that lurks behind every issue we discuss, and any philosophical or religious question touches upon, which is what we owe the universe, its Creator if it has one, and each other. We can't learn everything about everything, and we must make choices what to spend our time on.

In the political system we inhabit, in the U.S. and other contemporary representative democracies, we choose whom to trust to make decisions for us. There is a tendency to think about our choices in voting as a process of simply matching up policy preferences, but that leaves out of consideration the very important human question of which candidate will actually act on his or her stated policy preferences and do so effectively.

In our awareness of the broader world, when we give our allegiance to science, it's good to have an idea to what sort of thing we are pledging ourselves. Different sciences are at different stages of development and are more or less ripe for further paradigm shifts. Those paradigm shifts may come more or less "off in the distance," where they may or may not affect how we solve practical problems. The paradigm shifts we've discussed in physics didn't change how civil engineers made their calculations, but the plate tectonics revolution in the 1960s did have practical ramifications for economic geology and hazards assessment, just to name two things. The human sciences of economics, sociology, and psychology are good examples of sciences that are ripe for paradigm shifts. Indeed, currently, they are in the really unstable situation of having multiple competing paradigms.

When we apply science to a practical question, like the issue of climate change, being a good intellectual citizen means gaining at least some awareness of the different parts of the problem and the degree to which our experts can express certainty on each issue. Climate change requires at least three big components. First, we need the basic thermodynamics of how air and water respond to heat, how they move and mix. On that abstract level of physical laws, we have great certainty. Second, we need detailed data on the temperatures, wind speeds, air composition, etc. all across the planet. On that level, we have a great deal of data, but not as much as we could conceivably want. Third, we need models that run on as dense as possible a cluster of node points, which is to say models that divide up the atmosphere, land, and oceans into the largest number of little boxes possible; and likewise, models that take into account as much of the physics as possible, and not just a few of the elements. This is the really hard part, even with the computing resources we now have.

Bill wraps up the episode by noting how daunting we have made the question of intellectual citizenship and also how important the question of models is whenever we try to apply science...and maybe any body of intellectual knowledge...to our problems. We will take these questions as our point of departure for the next episode.