Episodes

Monday Aug 20, 2018

Episode 021 - Hypocrisy and Geology: Battlegrounds Between Faith and Science

Monday Aug 20, 2018

Monday Aug 20, 2018

Bill and I start off by discussing some of the reasons why there is such animosity against faith and such a tendency to credit the claim that science and religion are mutually incompatible.

I think we miss a great deal of the point if we do not take into account the relentless critique Christianity has mounted OF ITSELF over the past half millennium. The Reformation splintered the Christian nations and sparked unprecedented bloodshed between Christians. There had been terrible episodes before, but these wars, culminating in the Thirty Years' War, were on a new scale. The massive hypocrisy of Christians killing Christians, and the continuing hypocrisy of Christian clergy enjoying positions of wealth and privilege in both Catholic and Protestant nations, sparked further critique, leading to the Enlightenment and modern liberalism and progressivism. I ask you...do you think anything like modern progressivism, which bases itself on advocating for the poor and the repressed, could have arisen except as a Christian critique of Christianity?

In any case, we continue down to the present to be living in the dwindling, waning days of that union between Church and State, even in the US, and the scandals from that are still with us, as we know this month in Pennsylvania and with the spectacle of Cardinal McCarrick. That provides powerful impetus to look for other sticks to beat Christianity with.

It doesn't help that there are also people, in numbers enough to be visible, who really do espouse a form of religion that is contradictory to science. The Bible itself makes no claim to be the only book worth knowing, but the post-Reformation world has quite a few people willing to make that claim on its behalf.

Turning back to the intellectual issues within the debate itself, I bring up the question: why does so much of the fracas around science vs. the Bible center on biology, when the real question is the Bible vs. geology? Biologists have no real basis for determining the rate and overall progress of evolution if they were not given access to the fossil record and geological time scale...by geologists. Further, there is a great deal more of the Bible that makes claims about geology than about biology. (It's still an extremely small fraction, but of that small fraction...)

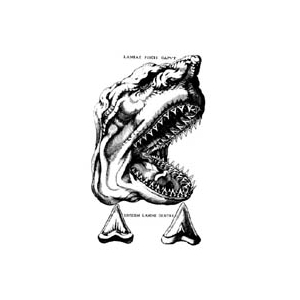

In fact, as the science of geology got started with people like Nicolaus Steno (his sketch of a shark and shark's teeth is the image for this episode), one of their first tasks was to try to evaluate the record of stones and sediment for evidence of Noah's Flood. One of the first crises in geology was dealing with the failure of this quest to find evidence for a global flood (which may or may not be an accurate translation of the intent of the writer of that part of Genesis, but that's another story).

Monday Aug 13, 2018

Monday Aug 13, 2018

Today was just one of those days where I needed a script to get through a three minute intro. I summarize the interview afterward.

Paul: "Welcome to Episode 20 of That's So Second Millennium.

"I'm Paul Giesting, a geologist, researcher, consultant, writer, and your co-host on this journey through the beautiful frontier country between science, philosophy, and religion as they stand here at the beginning of the third millennium. My opposite number is Bill Schmitt, a journalist, radio personality, and dab hand with the accordion.

"This week Bill managed to snag an interview with Father Robert Spitzer, who runs the Magis Center out on the West Coast and is the host of Father Spitzer's Universe on EWTN. He's published a number of books, which tend to have provocative titles; the one that I've read is called New Proofs for the Existence of God. That's an exciting read for anyone interested in the subject matter of this podcast, and travels through scientific and philsophical and mathematical arguments like the debate over fine tuning--whether Someone had to deliberately create the universe as it is, given how tightly constrained many physical constants seem to have had to be in order for any of the complex structures of atoms, planets, and stars to form and allow the appearance of life--and the question of whether it really makes any sense to speak of a "reverse infinity" and a universe that has always existed. Indian thinkers, Plato and Aristotle, and even Thomas Aquinas either thought that the universe has always existed or at the very least that there is no logical contradiction in saying that it could have always existed in time, even while Aristotle and Thomas asserted that the universe could not have an infinite chain of causes and needed a Prime Mover. Spitzer, in New Proofs, brings forward arguments from the philosophy of mathematics that perhaps this idea of a reverse infinity is not really logically coherent at all...a topic for one or more future podcasts.

"For today, Bill talked to Father Spitzer about the state of culture and the demographics of young people leaving the practice and even the identification of faith and citing as one reason the perceived contradiction between science and faith, initiatives to fight that, and the real absurdity of this perceived contradiction. With that I'll let Bill take it away."

Bill: Introduces our podcast and the motivations: value to filling holes in the culture, addressing the young.

Spitzer: Most recent Pew survey in 2016 comments on the high fraction of young people not just leaving the Church for a while, not just leaving a Church, but leaving faith altogether and becoming agnostic or atheistic. 49% of those leaving cite the perceived contradiction between science and religion as a key reason.

Bill: Proposes two reasons why that might be: was this gap "percolating" for a long time and just not being addressed, or is there a recent development pushing this.

Spitzer: It's both. The gap has been there for a long time [below the surface]. There are a lot of internet resources, social media outlets devoted to pushing an atheistic worldview. This feeds back into schools. Science teachers and professors that publicly espouse atheism meet audiences that are already primed that direction and certainly have no answers to contradict what they're being told.

One of his initiatives is crediblecatholic.com, where there is a bundle of resource modules presenting core arguments for the consistency of the Catholic faith and science and even arguments that discoveries in science point toward faith, not unbelief, in a Creator as the more sensible interpretation of reality. Pushing to get this curriculum into every diocese and every confirmation class and Catholic school curriculum.

Example topics: the Shroud of Turin, evidence for an intelligent Creator, near death experiences, evidence for a transphysical soul, 20th and 21st century accounts of miracles that have been thoroughly investigated with scientific methods.

Bill: The New Atheism is almost built on being shallow, on an attitude of mockery rather than on a serious analysis of evidence. This approach is the opposite: really multi-faceted.

Spitzer: Cardinal Newman talked about the "informal inference" to faith. It's not one argument; it's about twenty lines of reasoning. In our day we have if anything more of these, all the way from philosophical to scientific arguments to faith on the large scale to countless examples of miracles that have withstood thorough scrutiny by skeptical researchers. This is what the Credible Catholic approach is trying to convey.

We've tested the curriculum on beta groups of students in Austin, New York, Los Angeles and gotten remarkably high marks from these groups (97% positive / very positive, rated anonymously).

Bill: Pope Benedict foundation awards for "expanded reason" and the problems with positivism, scientism.

Spitzer: The logical contradiction at the very foundation of Vienna Circle positivism: it makes the self-contradictory claim that "the only valid knowledge is scientifically verifiable knowledge"...good luck checking that statement by scientific methods. That's a school of thought from the turn of the 20th century; we in the Church have been wrestling with it for a long time.

Reminiscence about a debate on Larry King Live with Stephen Hawking (et al.) and the claim that science had replaced philosophy...this is likewise straightforwardly impossible; science and philosophy do fundamentally different things. For that matter, so do science and mathematics.

Bill: A contradiction that I see more than ever: our culture and educational system is arguing for atheism and at the same time dumbing down our understanding of basically everything, while there is a growing s(S)ociety of Catholic Scientists...[a quick back and forth]

Spitzer: Artificial intelligence's potential is overrated when it is claimed that it can become creative in anything like a human fashion. It can't find new truths; they don't love [or will] or have any of the transcendentals. Computers are marvellous tools that, *in tandem with us*, can take us to new places we could not get without this kind of effort multiplier...

Studies on religious and non-religious affiliated groups, with the latter having much higher rates of maladaptions: suicide, substance abuse, impulsivity, depression, etc. Augustine's comment about our hearts being restless until we rest in God seems to be empirically corroborated.

Closing: CredibleCatholic.com, Notre Dame initiatives to educate high school science teachers on the interrelations between faith and science.

"So there we have it. I also want to thank Father Spitzer for taking the time to give this interview. We hope to present many more interviews as That's So Second Millennium matures and gets going. The point of the podcast has always been to get conversations started about these core issues, whether and how to be a logically coherent believer in the modern age. It's started with these conversations between Bill and I, but the point is to move outward and engage with more of you. The time is rapidly coming to expand this outreach another step or two, through social media and ordinary human interactions. Right now you can check out the Facebook page for That's So Second Millennium, and you can leave ratings and reviews on one or more of our podcast servers, Apple, Google Play, Stitcher, or Podbean."

Monday Aug 06, 2018

Episode 019 - Conclusion: SCS Conference

Monday Aug 06, 2018

Monday Aug 06, 2018

We pick up from last week's episode with the next speaker. Kara Lamb followed Andrew Sicree; her research is about the atmosphere and climate. She mostly talked about climate, and got a ways into specifics about her research on black carbon soot in the atmosphere. She did stop to draw a parallel between Laudato Si and Pacem in Terris, that in both cases the Popes stopped to address humanity at large and not just the Church.

Juan Martin Maldacena was after her, and was presented the St. Albert Award. You don't schedule Juan Maldacena and not have him talk about his own physics research; he is famous for research on workable forms of string theory in anti-de Sitter space and some results on the shape and nature of black holes. His talk was very technical and rather hard to summarize, but an intriguing aspect of it was the recurring notion that black hole singularities and the original singularity of the Big Bang might have a lot in common.

Sunday morning after Mass Michael Dennin led off with a talk structured around a book called "The Big Picture" by somebody I think I've heard of but don't know why named Sean Carroll. In this book Carroll apparently divides reality into "poetic naturalism", where "poetic" means "stories we tell ourselves about large complicated objects" and "naturalism" means "quantum physics, which is actually reality". Dennin made four points:

- Emergence. Reality does not appear to be just quantum physics (or, I would elaborate, not even just a unified theory that somehow gets gravity and relativity united with quantum physics). There are really new laws that emerge as you go to larger, composite, varied objects...the laws of thermodynamics, entropy in particular, are an example.

- Physical reality. It's a little much to talk about "reality" so cavlierly; it ignores basically metric tons of philosophical questions people have spent centuries debating. Is physical reality basically sense data? Is it the particles we theorize to be out there to explain, ultimately, our sense data in the context of the experiments we do and the natural objects we observe? Isn't there nonphysical reality: mathematics, wavefunctions (they can't be completely physical), conscious reality / qualia? How can we be sure there aren't nonphysical "forces" acting on physical objects? In some way, don't they have to? (mathematics and logic in some way constrain reality, that's a rumination of mine while writing this)

- Free will...the Comptonesque observation that quantum physics leave room for this nonphysical soul or mind to affect the physical body

- MIracles. Dennin actually led off the talk with an exercise, asking us to define miracles, and then he went on a fairly vigorous campaign against the idea that miracles ever incorporate the violation of physical law, or at least that they require it, that that should be in the definition. I noted "Contrasting focus on God's will/purpose..." but I cannot really reconstruct what he seemed to be driving at.

Craig Lent, a professor at Notre Dame, went next and gave an interesting talk that interfaced with others. He actually seemed to conflict with Barr in that he commented early on that the "state vector," which had be be the wavefunction since it had the same Greek letter psi for its symbol, contained all the information possible to have about a system and not just one observer's (the concept Barr used). He also addresses the measurement problem, but my note broke off mid-sentence. He went on to summarize the content of Scarani's talk, that Bell inequality experiments all show that the universe is not deterministic. He then addresses the claim that while atom-scale particles show quantum indeterminism, larger stuff does not, and nerves are enough larger that the human brain must be deterministic. That's probably not true; even 10,000 atomic mass unit molecules like neural transmitters show quantum behavior in experiments. We are left again with the Arthur Compton point that while obviously physics constrains us, our brains are not deterministic machines; if our souls are not affecting them, then at the very least some of their functionality is random.

The final talk was by (Padre) Javier Sanchez-Canizares on "Mind, Decoherence, and the Copenhagen Interpretation." This again comments on many of the topics in previous talks. Unfortunately the talk seemed to paw about problems already discussed without coming to any new realizations. I cannot tell from my notes whether I learned anything about decoherence, which I was really hoping to do; I think I had to look it up afterward, and even then the answers I've found so far are not satisfying. He asked the "Wigner's friend" question that Barr mentioned about the "cut" between the observer and the system in a quantum physics observation. He also made some intriguing comments on the nature of classical physics: if quantum physics is reality, why is it so hard to get rid of classical physics terminology? We still describe things that way. A recent physicist, Zurek, comments that classical physics entities somehow embody a "survival of the fittest" (the sort of comment I start questioning for influence of the divine name of evolution). Heisenberg apparently said that classical physics terms are just unavoidably part of how humans interact with the world.

Monday Jul 30, 2018

Episode 018 - SCS Conference: Peter Koellner, Andrew Sicree

Monday Jul 30, 2018

Monday Jul 30, 2018

As I've mentioned, we batch recorded the last four episodes about a month ago, and so we opened with a retrospective on the conference as a whole and its significance.

We moved on to discuss Peter Koellner. Koellner was the next talk and probably deserves his own podcast. I have gotten his lecture slides from him but won't have time to analyze them for a few weeks. The short version for now is that he gave us some perspective on Godel's theorem, a result in mathematical logic that many (including many agnostics like the physicist and mathematician Roger Penrose) have taken to imply that human thought must transcend any finite logical system that could be, say, programmed into a computer: in other words, the human mind is not a computer. Koellner argued, in large part from Godel's own writings, that what he actually proved is probably that EITHER human thought transcends the mechanical OR that there are mathematical truths that transcend mind. This is potentially a blow to a number of people who rely on the argument to prove our superiority to our own machines, but I myself find either conclusion to be exciting.

Andrew Sicree was next. He gave this tremendously gung-ho talk about Father Nick Steno, the 17th century member of the founder's club of geology (I think that's fair; Sicree basically called him the founder, singular). It was mostly fairly familiar stuff to me, some of which I have lectured on myself in classes in passing. He is still known today for Steno's Laws of stratigraphy (i.e., the relative ages of rocks):

Principle of Superposition

Principle of Original Horizontality

Principle of Inclusions

and in mineralogy he is remembered for the Law of Constant Interfacial Angles, basically the very dimmest beginning of crystallography. However, Sicree gave some time to other aspects of Nicolaus Steno's thought and also to his career as a layman and cleric. I only thought I was a Nick Steno fan before this talk. Andrew Sicree is the real deal.

Monday Jul 23, 2018

Episode 017 - Aaron Schurger at SCSC: Fifty Years Without Free Will

Monday Jul 23, 2018

Monday Jul 23, 2018

It's a short one this week. We discuss the talk at the Society of Catholic Scientists Conference by Aaron Schurger with the delightfully provocative title "Fifty Years Without Free Will." (Those of you who are similiarly obsessive about grammar will appreciate my deep feeling of conflict about capitalizing the preposition "without"...one is not supposed to capitalize prepositions, yet it looks awful to have a seven letter word not capitalized. It's not capitalized in my notes, but it was in the program.)

Notes I took during the talk, which for this podcast pretty closely follows the drift of our conversation:

Distinction of the "neural decision to move"

Readiness potential with ~1 sec onset time

Libet et al 1983 Brain 106:623-42

asked subjects to report when they decided to move

happened ~3/4 sec after readiness potential, only ~1/4 sec before the movement

Taken by many as proof that "there is no free will"

Alternative interpretation: the "readiness potential" is random drift of neuron voltages

under the weak imperative to move

Need to pay careful attention to experiment setup & analysis of data [Paul's comment today: *always*]

Problems with only analyzing data time-locked to movement and extracted

Monday Jul 16, 2018

Monday Jul 16, 2018

Dr. Scarani opened the talk by noting a paper he placed on arxiv.org about Aquinas and the sense that the universe would not be perfect without randomness.

He moved on to discuss randomness in two senses: Process Randomness, which implies that there is an observer unable to predict the output of the process; and Product Randomness, the lack of structure of a product, which turns out to equate with the need for a very long algorithm to replicate the product. Products are tested for randomness by a battery of statistical tests. He gave an equation embodying a mathematical definition of [product] randomness. Not being an information theorist, I had not seen it before.

He went on to note the difference between the randomness of classical physics, which is always about a lack of complete information about a system. If one had that information, the system under the classical assumption would be perfectly defined, and as we have noted a number of times, Einstein among others desperately wanted to get back to that deterministic paradigm. "The Old One doesn't throw dice."

The core of the talk was what Scarani called a "high school level" presentation of Bell's theorem. I would like to meet the high school student who could follow it at the speed at which he gave the talk, but probably could have unpacked it given a couple of hours to do so even at that age. Bell's theorem is one of those cunning little mathematical gems that seems to prove the unprovable, namely, to make a prediction about something going on in a process one by definition cannot see into. Bell sets up a statistic that, if there are hidden rules governing physics below the scale at which the uncertainty principle lets us see, must nevertheless in real experiments end up being less than 2. Since the 1980s a series of ever more careful experiments have been done, and the answers in the papers Scarani reviewed had answers between 2.4 and 2.7; the answer is never below 2. According to Bell's theorem, this means that there is a really random process going on down there, and not just random products.

At the end, as we discuss in the audio, Scarani ran down the list of remaining possibilities for understanding the quantum foundations of the universe:

- There is real randomness.

- "Superdeterminism." This depends on breaking an assumption of the Bell theorem, which is that the quantum process is being fed input that itself is not really random from the perspective of that process, which would seem to imply some sort of physics puppet master controlling the experimenter.

- The many worlds hypothesis, again something we have mentioned a number of times. I am still not buying that stock.

- The only allowable sort of hidden variables (the name Bohm is attached to the most commonly discussed of these) would require particles communicating with each other at infinite speed, "deliberately" trying to wreck the experiment, and with the interaction hidden in a way workers in the field have called "conspiratorially hidden." I.e., we would be living in a universe run by a sort of Cartesian evil deity.

On that theme, note that I blundered off into talking in a sort of Cartesian dualist fashion about the relationship between soul and body there after the 14 or 15 minute mark.

Monday Jul 09, 2018

Monday Jul 09, 2018

In today's episode we discuss Stephen Barr's talk at the SCS conference on June 9. His topic was the observer question in quantum mechanics. The observer problem is closely tied to the issue of probability and wavefunctions. We spend quite a while discussing what this problem is and how the question arises in the context of experiments like the famous two-slit experiment. The example of "Schrodinger's Cat" is an attempt to make this problem more understandable to the non-quantum mechanic. The cat is in some uncertain state, neither alive nor dead, until the observer opens the box and "collapses the wavefunction" to either a live cat or a dead one. In a two-slit experiment, a particle exists in some distribution of possible positions until an observer collapses the wavefunction and "forces" it to one tight range of locations (and for that matter momenta...).

This is very weird. Barr cited a long list of quantum theorists (von Neumann, London, Bauer, Wigner, Peierls, and others) who considered the problem and whether mind as such is crucial to whatever it is that does the measuring and observing to collapse quantum systems. Wavefunctions, with their consequent probability distributions, evolve according to Schrodinger's [or Dirac's?...a question I've had in the back of my mind many times...] equation with no internal mechanism to cause this collapse. Clearly two very unlike things interact to form quantum mechanics as we know it, as von Neumann stated explicitly (calling the observer / collapse phenomenon "process 1" and the wavefunction evolution "process 2").

It is clear that we can shift our mathematical formalism to incorporate any physical measurment device into the "system" and thus recognize it to be in the realm of wavefunction behavior. There is the "Wigner's friend" thought problem where even a human observer of an experimental setup can be placed in the "box" from the point of view of another human observer.

When we consider the observer problem from the point of view of a descriptive science (geology, astronomy, zoology, etc.) there is the immediate and rather alarming philosophical question: What was happening to, say, this star or tectonic plate or ancestral population of invertebrates before there was an observer to collapse the wavefunctions? Someone raised this question with Dr. Barr in the question and answer session after the talk. There is a phenomenon called "decoherence" (warning: that link is informative in places but far from the clearest read) which occurs for systems that are very open, interacting with their surroundings. Broadly speaking, the observable in question can trade uncertainty with its surrounding and settles down into a tighter range of possible states, simulating to some extent the effect of an observer collapsing the wavefunction. However, the two phenomena are not the same.

Monday Jul 02, 2018

Episode 014 - Ed Feser's Keynote at SCS

Monday Jul 02, 2018

Monday Jul 02, 2018

In this episode we begin a series of recaps and discussions of the issues brought up by individual lecturers at the Society of Catholic Scientists conference on June 9 and 10. We start with Ed Feser's keynote, "The Immateriality of the Mind."

Feser's objective was to highlight how our ability to be rational, and in particular for our thoughts to mean something unambiguous - even in the face of our inability to express ourselves in a completely unambiguous way in our spoken or written words - makes it difficult to maintain a purely materialist / physicalist view of human minds and therefore of the universe they inhabit.

At the outset he noted that rationality tends to occupy less attention in philosophy of mind and matter than two other properties, consciousness and intentionality, which seem widely taken as more difficult to explain by our contemporaries. For ancient and medieval philosophers, however, rationality was probably the clearest indication that the human mind is not some sort of solely physical mechanism.

Feser presents an argument via James Ross (Thought and the World) to try to bring this older consensus into the mainstream. It can be presented thus:

- Formal thought processes can have an exact, unambiguous content.

- Material signs and processes never have unambiguous content.

- Formal thought processes must employ an element not dependent on materials signs and processes.

We discuss Feser's points and a few of our own in favor of the two premises: our inability to be sure of the content of arithmetical symbols used outside our own range of experience, the ambiguity of translating ancient languages like Linear A, and the absurdity of believing I can't ultimately know what I'm thinking about.

Monday Jun 25, 2018

Monday Jun 25, 2018

Intro

Overview of the conference - schedule

Talks

Edward Feser & connections to Bishop Barron

Theme: Human Mind & Physicalism

Development of the problem and the amazing change in intellectual climate since the 19th century

Laplace and absolute determinism - 19th century consensus

Quantum mechanics demolished this intellectual basis for determinism, although it is clung to fiercely down to the present day, including the profoundly horrifying "many worlds" hypothesis

Bell inequality and the talk by Valerio Scarani about the closing of the loopholes that would allow a "hidden variables" interpretation of quantum mechanics (which would also save determinism, in a much saner way than the "many worlds" hypothesis)

Materialism and "spiritualism" (if you will) are on an equal logical footing, even if cultural issues continue to propel many scientists and intellectual citizens of the contemporary world away from belief in extramaterial beings

Society of Catholic Scientists as a place of refuge from this social pressure toward materialism

The gap between spiritual and material in ancient thought versus modern thought

The problem of qualia, choice, and consciousness and the lack of an actual materialist model for these, as opposed to evasive and reductionist language

On the other hand, the reality of a physical manifestation of all (or nearly all) mental phenomena, the dignity of matter in this detailed participation, and the absolute need for human souls to have bodies in order to be complete human beings (in contrast to Manichean, Platonic, or Cartesian dualism)

The scholastic notion of the human soul as form of the body

The Aristotelian soul / souls

Are vegetative (and animal) souls the forms of those bodies...are those essentially their genetic structure?

This ties back to our existing discussions about "hylomorphism for the third millennium" (so to speak)

The need for a new metaphysics and philosophy in general to rise up and deal with the strange new world that modern science has brought to our attention.

The scholastics, Aquinas of course being the one we remember, had a philosophy that was capable of being constructive...Chesterton's comment that modern philosophers ask us to accept some crazy thing in order to found their system, while Aquinas' starting point was common sense.

The difficulty of thinking and doing interdisciplinary scholarship in the modern world, despite decades of recognizing that we need to do it, due to the volume of human knowledge today and also the whole economic and sociological apparatus that depends on measuring scholars' output somehow...which is tremendously easier for single-focus scholars to maximize.

There is a unique joy that we can have as scientists of faith...both in our subject matter and in our fellowship with each other.

Our next few episodes will look at the subject matter of specific talks at the conference.

Monday Jun 18, 2018

Episode 012 - Society of Catholic Scientists

Monday Jun 18, 2018

Monday Jun 18, 2018

Not to be confused with the League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, although one would understand the mistake.

Bill interviews Paul about his experience and observations at the Society of Catholic Scientists conference that took place June 8-10 at the campus of Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C.

The SCS is a very young organization. Its first president is Stephen Barr, a physicist at the University of Delaware. Its first conference was in April 2017 in Chicago. The theme of the 2018 conference was "The Human Mind and Physicalism"--physicalism being a somewhat more precisely defined term than its synonym, materialism. (Believe it or not, some folks at the meeting thought those two elements in the title were probably incompatible.)

Paul discusses the meeting and the variety of scientists he saw and met there, including Barr, Juan Martin Maldacena (a prominent string theorist), Aaron Schurger (a neuroscientist), and more. Bill and Paul do a little digging and comment on motivations for the group, including the desire for fellowship (like the existing group, Catholic Association of Scientists and Engineers) but also to band together against the folly of the existing culture and its tired, hugely outdated idea that science and faith (certainly the Catholic faith) are logically incompatible. GK Chesterton was quite right when he commented that the quarrel between science and religion was properly left to prematurely arrogant scientists and sola scriptura fundamentalists back in the NINETEENTH century. It's the twenty-first, now, and we should get ourselves to the business of putting this to bed.

Paul elaborates on this final fact at some length, discussing the parallels between the current day and the scholastic synthesis of the thirteenth century. Odd, is it not, that in the broad sweep of history, Aristotle and his universe existing indefinitely backward in time lost out to the stories of a bunch of Hebrew peasants who thought the Prime Mover had actually created the world at a specific point...